The student experience during COVID-19

12.01.2021 • 7 minutes

From immediate impact to long-term implications: 4 articles exploring the effects of the pandemic on the student experience.

One year. It is hard to believe it has been one whole year since we first started hearing of the Coronavirus. Harder still to believe that we haven’t yet heard the last of it. Perhaps, when the news came that schools and shops would have to close down “for a few weeks”, much like Mariah Carey’s All I want for Christmas is you, none of us thought the virus would stick around for as long as it has.

In these strange times, the student experience has been a central topic of discussion. Since no one knows how long these circumstances will last, we thought we’d explore what it meant to be a student in 2020, and what the future holds for those who were. This series is made up of 4 articles, each tackling a separate aspect of this vast subject:

- The immediate impact of the crisis on the student experience,

- The risk the crisis poses to students’ mental health,

- What the student experience will be like after COVID-19,

- And the potential consequences of the pandemic on their careers.

Of course, as with all things, we must start at the beginning.

Why focus on the student experience?

While all sectors of the economy have been affected by the crisis, few industries have been disrupted like education. Course design and preparations, student hopes and expectations, all were spoiled when teachers and students learned that things would change - drastically and indefinitely.

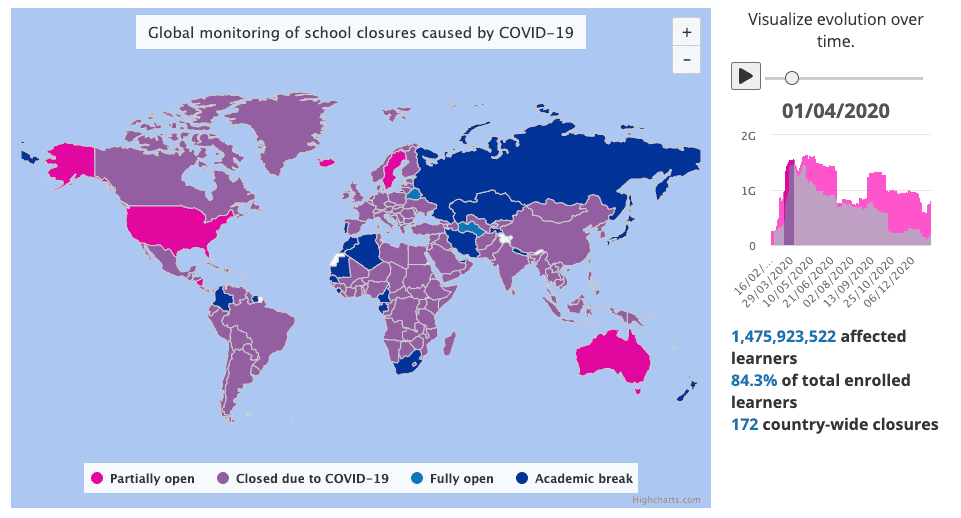

By March of 2020, 22 countries had announced or implemented school closures, which meant the Coronavirus had already affected the schooling of more than 300 million students. All in all, according to UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition, “more than 1.5 billion students and youth across the planet are or have been affected by school and university closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

COVID-19 Impact on Education, data from April 1, 2020. Image found on https://en.unesco.org/

Despite being young and therefore not particularly at risk of catching the virus, students have experienced the dramatic effects of COVID-19 during the first half of 2020 (Aristovnik et al., 2020). Indeed, students - particularly those in higher education - are the ones with the most to lose in this crisis. Not only can the lack of social contact be detrimental to their mental health, but the quality of their education is being threatened - and with it, their future prospects.

To explore all these questions, doubts, and uncertainties, we talked to a recent graduate from the London School of Economics, whom we’ll call Kate. Kate was studying for an MSc in International Relations when the pandemic struck, and like so many others, she had to face the stress of remote lectures and exams, limited access to teachers and resources, and the challenge of motivating oneself to study and get some work done. Or, as she puts it: “Nothing to it.”

How has COVID-19 affected the student experience?

Students faced with uncertainty: January - March 2020

Before it became the devastating pandemic it is today, the Coronavirus had already worked its way into the minds of students. Kate’s Lent term had just begun, in late January, when she received the first of many university-wide email updates on the spread of the virus. It stated that the risk to the UK was low, and that day-to-day activities would proceed as normal. That would soon change.

As the number of cases increased throughout February, students had no clue when or for how long things at their school would change. Kate, like everyone else, was left wondering. However, change was coming: that much was certain.

Ironically, uncertainty was perhaps the hardest thing for students to deal with during this period. They relied on clear and timely communications from their school, which were sometimes lost in overflowing inboxes or spread across several digital platforms, further fueling their anxiety and stress. Still, according to the 2020 National Student Survey, “75% of full-time students in England agreed that changes in the course or teaching had been communicated effectively”.

In the end, it was decided that all teaching activities would be delivered online for the remainder of the academic year. Students had no idea how this would work, and neither did many teachers. Graduation ceremonies would be postponed, the dates and formats of the Summer Term Examinations were still to be determined, and the release of the highly anticipated video game Cyberpunk 2077 would be delayed again. All of the above were equally devastating news, to be sure.

From the classroom to the screen: March - June 2020

The move to online courses happened very abruptly, as countries closed down schools and issued stay-at-home orders. Despite the herculean efforts of the worldwide teaching community, many online courses left some things to be desired.

“During seminars, we were encouraged to discuss and exchange in break-out rooms on Zoom”, says Kate. “This went well, all things considered, but it still wasn’t the same as in-person exchanges, especially when discussing sensitive subjects like people’s personal political views. It certainly stifled some communication.”

Considering these challenges in online discussions, Kate was thankful that the shift to distance learning happened as late as possible, because it had allowed her the time to establish some personal relationships with her peers face-to-face first. This made them more inclined to share with and respond to each other, while the distance made it more difficult to connect with students they hadn’t met before.

According to a study conducted in an American higher education institution, “many students reported that their ability to work with peers, maintain interest in their classes, and feel a sense of belonging in the campus community suffered during the spring 2020 term. […] Students also relayed the negative impact that emergency remote learning had on the social aspect of their learning, which had repercussions for them both on the academic and socio-emotional levels.”

Another finding of that study resonated with Kate, namely that with the move online, students wished for more flexibility regarding course expectations and requirements. While the timing and format of assessments were revised, she feels the expectations and requirements of the exams could have been better adapted to reflect the more challenging conditions under which students were sitting them.

Student satisfaction

In the UK, the National Student Survey showed a minor drop in the overall satisfaction of students with their course (from 84% in 2019 to 83%), as well as with the organisation and smooth running of their course (67% of full-time students in England were satisfied, compared with 70% in 2019).

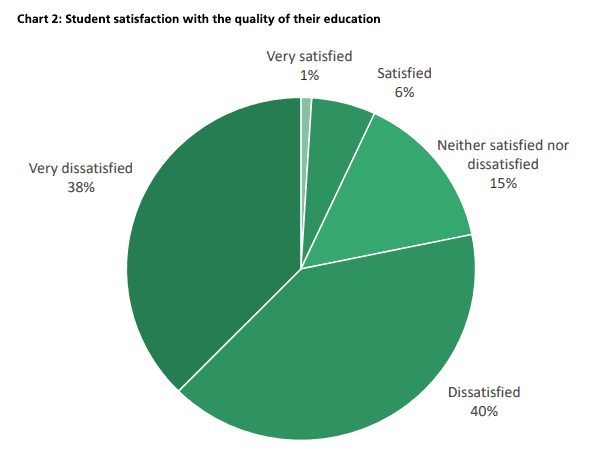

By contrast, in another survey, by the House of Commons Petitions Committee, the vast majority of students who responded said they were “dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the quality of education they were currently receiving.”

In Kate’s experience, students were understanding of the difficult circumstances under which their school had to make decisions, though many still thought certain decisions lacked empathy for what they were going through themselves.

Survey on student satisfaction, led by the House of Commons Petitions Committee. Image from https://committees.parliament.uk/publications

What’s next?

2020 was a rough year for everyone, and while there certainly are reasons to be optimistic about 2021, we are still dealing with a pandemic. Lockdowns and social distancing are still part of our daily lives, and the popularity of “free hugs” cardboard signs is at an all-time low. We’ve all felt the impact that this can have on our mental health, students and youth perhaps more than most.

“So, what can we do about it?”, I can hear you asking.

That is a question we will ponder in the next instalment of this series.

Make sure to follow us on social media, and subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out on any new content!

Writer

Gauthier Lebbe

Content Editor @Wooclap. I love to write, learn, write about learning, and learn about writing. And hit readers with puns they don't see coming. You know, sucker puns.

A monthly summary of our product updates and our latest published content, directly in your inbox.